By Kenn Taylor

Photie Man: 50 Years of Tom Wood at Liverpool’s Walker Art Gallery is the most comprehensive exhibition to date of the work of Wood, who is one of Britain’s most important image-makers. “It was something I wanted to do for the city,” Wood says. “The work was made here and I’ve had big shows all over the world; Moscow, France, China even, but not Liverpool.”

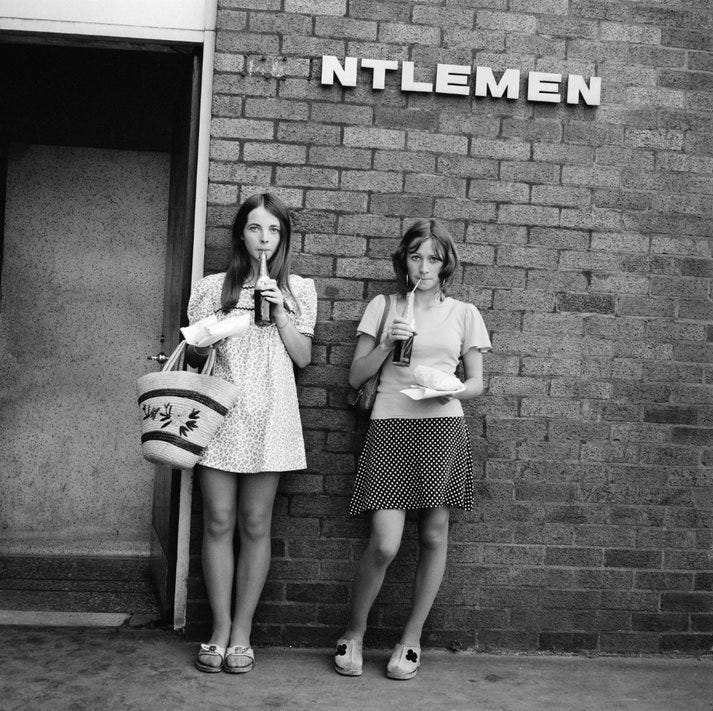

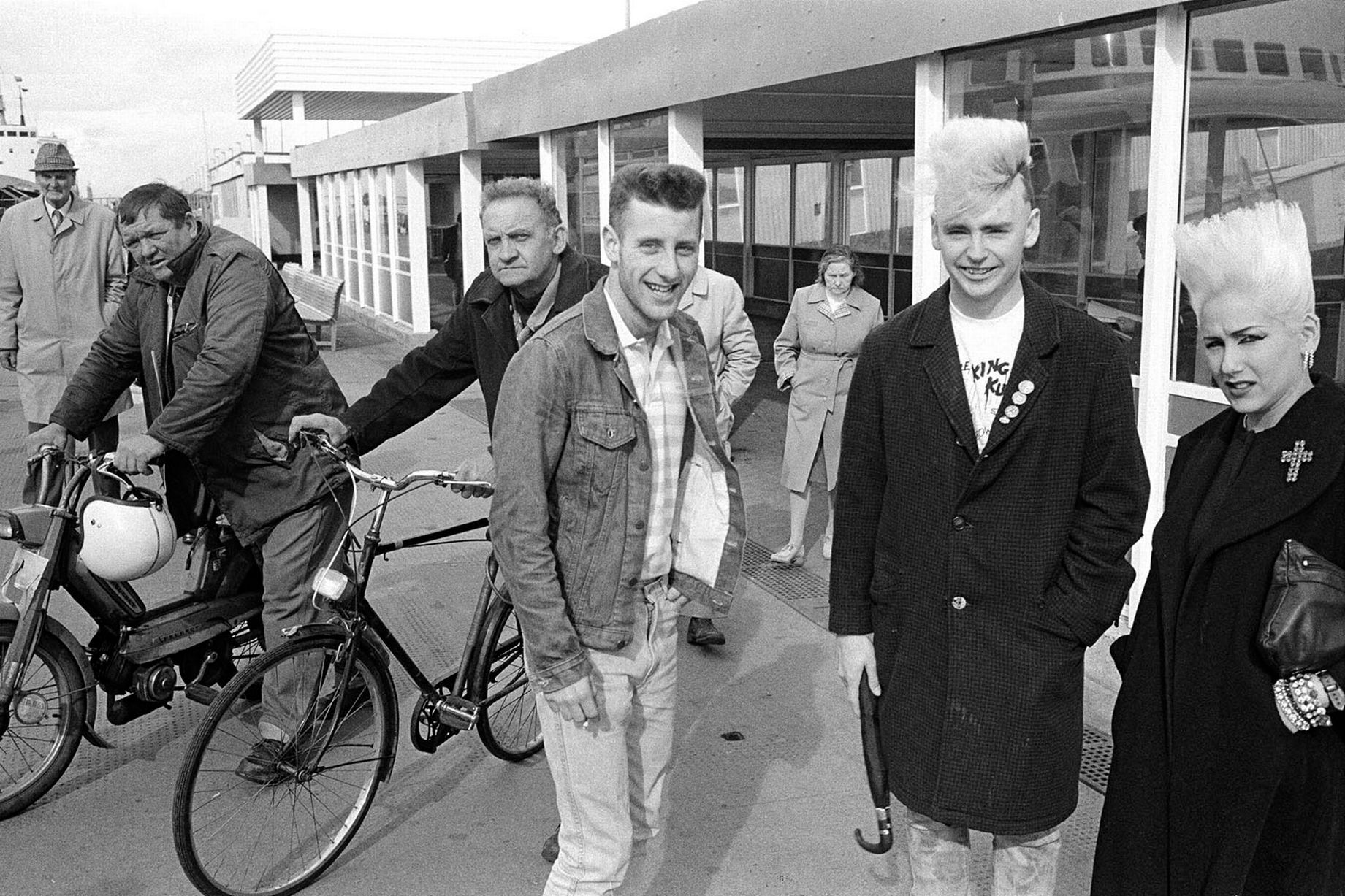

Wood’s images have until recently been more embraced by publishers and gallerists internationally. In the UK, he has sometimes been pigeonholed as a “documentarian of working-class Liverpool” rather than as a visual artist who creates striking, moving images that make people stop in their tracks, one of the issues being perhaps a middle-class dominated art sector struggling to grasp that working-class people could make and be the subject of great art without it needing to be social comment.

Boy with Fish, Secombe Docks 1980. Photo: Tom Wood.

“That lack of interest in Britain for a long time, it’s definitely partly a class thing. How I present myself but also the way photography is reviewed in a class way. ‘Not proper art’ and so on,” he says. For Wood, the contest between form and content was something interesting: “I thought a lot of stuff at art school, especially the conceptual stuff, was not real enough. It was like a game,” he says. “When I went out on the streets at the weekend, what I saw was more real and more interesting, but not in a documentary sense. I’m exploring my medium for sure, I’m an artist, but I’m exploring life as well.”

This expansive show features over 500 pictures, surveying his whole career, from images of his native Ireland and Leicester where he studied, to his current home in Wales and found photographs Wood collected as a young man. The largest element though are his photographs of Merseyside, where he lived for over two decades. One of Wood’s aims for the exhibition is to reconnect with some of the people he captured over the years and photograph them again. “That’s half the reason I have done the show,” he says. “To make that connection. You can leave details if you know people in the show.”

Lads at Railing, Scotland Road, 1987. Photo: Tom Wood.

The exhibition’s title comes from the nickname Wood was given in Merseyside as he became so familiar photographing the same communities repeatedly and building a reciprocal relationship with them. “I couldn’t do it otherwise,” he says. This extended even to taking wedding pictures for some of his subjects. Part of the power of his images perhaps comes from this deep familiarity. “Richard Feynman said he would not understand the real physics of a system until he had painstakingly isolated and calculated all the forces,” Wood says. “This is what I would tell myself as I was photographing the same subject year after year – whether it be women at the market, men at the football.”

Image from Photie Man: 50 Years of Tom Wood, Walker Art Gallery. Photo: Robin Clewley

Has looking back on his vast archive for this show changed his views on it? “Yeah, that’s the thing about photography. It’s not fixed, and life is not fixed. Things change, how it’s read changes,” he says. Not least a culture sector that now values photography, and this kind of subject matter, more. In the 90s, Wood managed to get an Arts Council grant after receiving a letter of support from Lee Friedlander. “It said ‘wonderful pictures. As good a set of pictures you see every five or ten years,’” only for Wood to then struggle to find anywhere to show the work. Does he feel vindicated by the growing interest from all quarters? He has three books due out this year alone. “A little bit,” he says. “Having Friedlander on board kept me going for a few years. A lot of people have supported the work over the years, not least the people in the pictures.”

Image from Photie Man: 50 Years of Tom Wood, Walker Art Gallery. Photo: Robin Clewley

“There’s something about the work that people from all over the globe connect to,” Wood says. “It’s very strange. I’m not impressive as a person. I think the work itself, or maybe Liverpool, maybe the people, I don’t know. But it does connect with people.”

Image from Photie Man: 50 Years of Tom Wood, Walker Art Gallery. Photo: Robin Clewley

This piece was published by AnOther magazine in June 2023.