By Kenn Taylor

In 2021, when we were all still reeling from the ongoing effects of the pandemic, a Kickstarter on social media caught my eye: a project to make a documentary about the life of photographer Tish Murtha, by director Paul Sng and Tish’s daughter Ella.

I knew of Murtha’s work through my deep interest in the photography of working-class communities and places. Yet, until I read the synopsis of the film, I’d not been fully aware of the scope of Murtha’s work, or the extent to which she was let down as an artist and a person by society.

After finally being able to view TISH in late 2023, these impressions have only been deepened by Sng’s powerful work, which is both a subtle, rich portrait of Murtha and hard-hitting in its moral and political message. While Murtha’s photography speaks for itself, Sng brings her life and the background to her pictures vividly into focus.

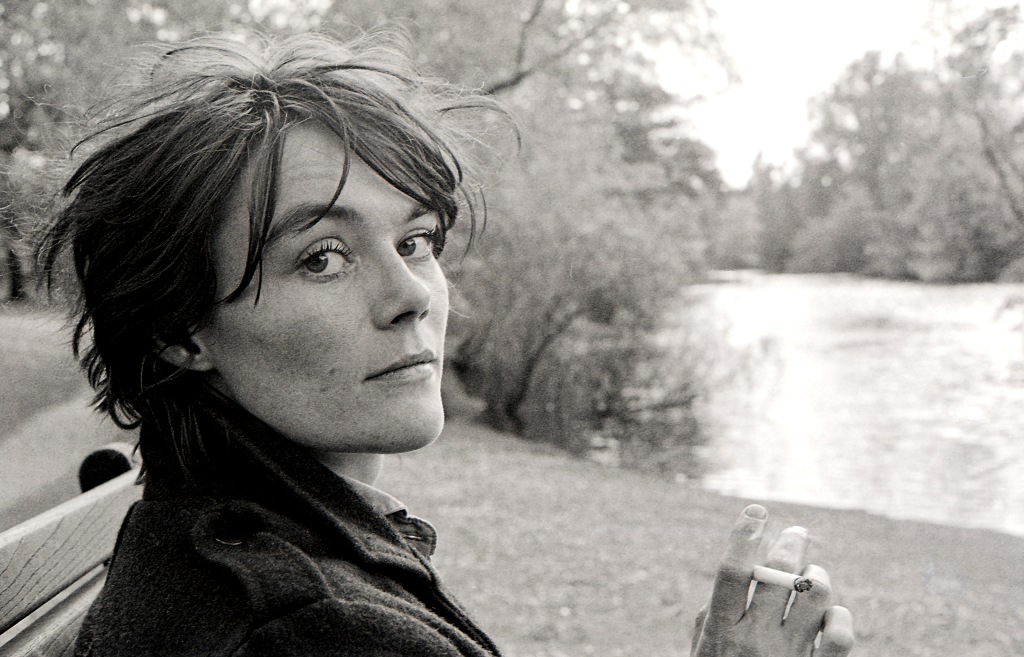

No moving image recording of Murtha exists, so her story is told through a mix of interviews with people who knew her and footage of Tish being played by Maxine Peake, whose voiceover readings of Murtha’s writing reveal it was almost as compelling as her photography.

In TISH, Murtha’s biography is brought to life in all its complexity. Born in 1956, Murtha grew up as the third of ten children in a family on Tyneside. She spent her childhood playing amongst buildings earmarked for urban clearance in Elswick – an area of Newcastle that was the backdrop to some of her most well-known images. Tish was encouraged by acquaintances to pursue her interest in photography and studied at a local college, where tutors advised her to progress to the highly regarded documentary photography course at Newport.

She returned to the North East with a growing reputation for her work, later moving to London where her photographs were exhibited alongside the likes of Bill Brandt. But Murtha struggled to make a living, especially after becoming a mother, leading to a return to the North East. Her work wasn’t exhibited again in her lifetime and she spent her later years scraping by, applying for any sort of low-paid job going, before dying in 2013 aged just 56.

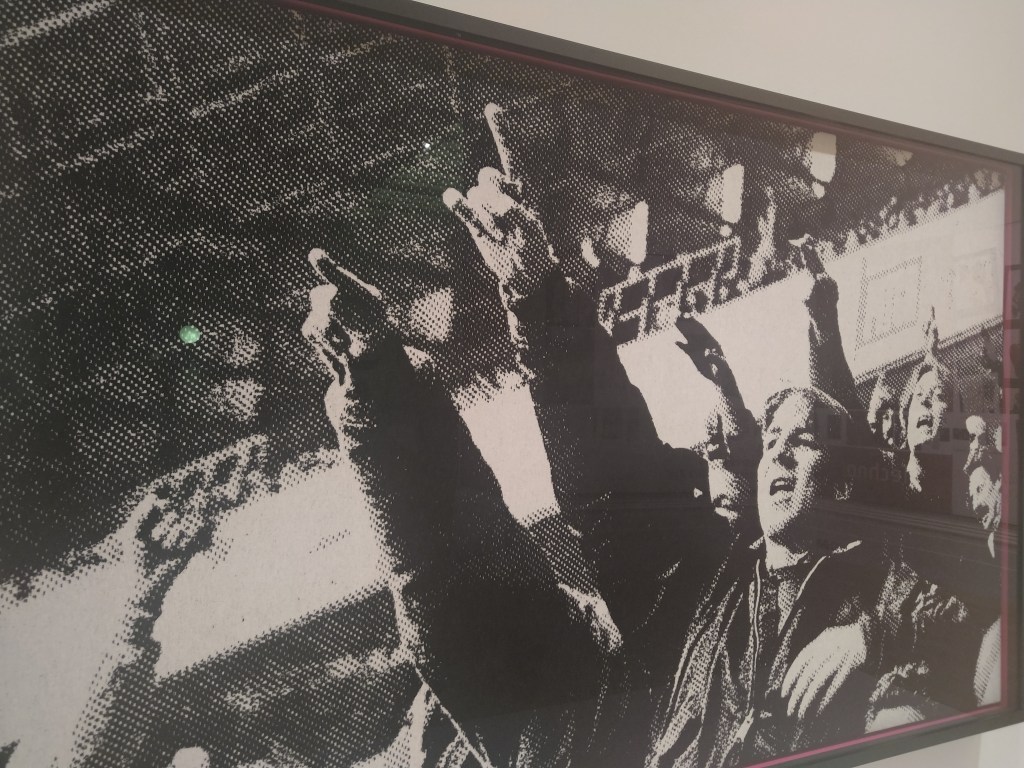

The film explores the driving purposes behind Murtha’s work, taken largely from within communities she herself inhabited. She captured and celebrated individual characters and communal experiences, even as she critiqued the situations her subjects found themselves in. Sng traces Murtha’s creative growth – and how that creativity was battered down by circumstances – as well as her anger at the scourge of mass unemployment and how it damaged lives and communities.

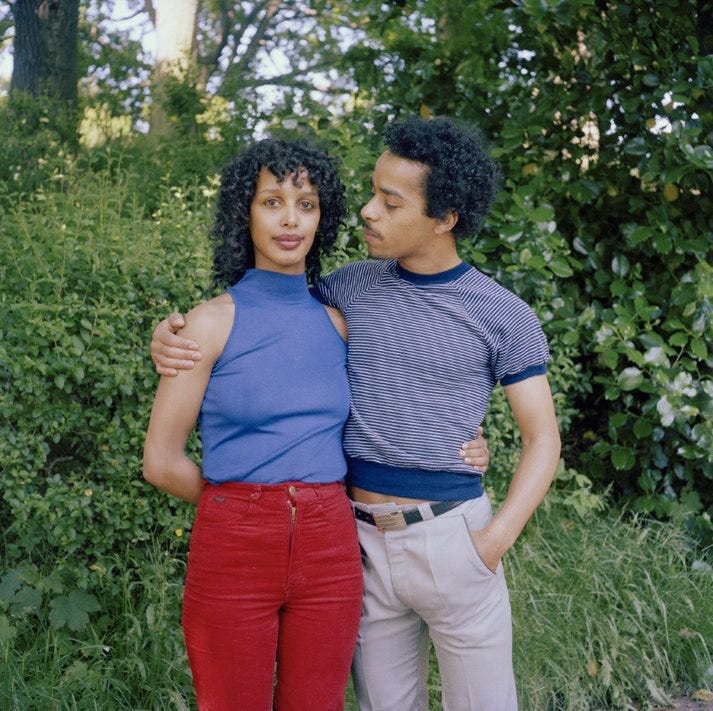

After moving to the capital, Murtha photographed people who made their living in London’s nightlife, some of whom she lived with. Her ability to immerse herself in this very different world and portray it just as vividly demonstrates her talent. Yet this nightlife project was to mark a high point in terms of her recognition within the cultural sphere, one she was unable to reach again during her lifetime.

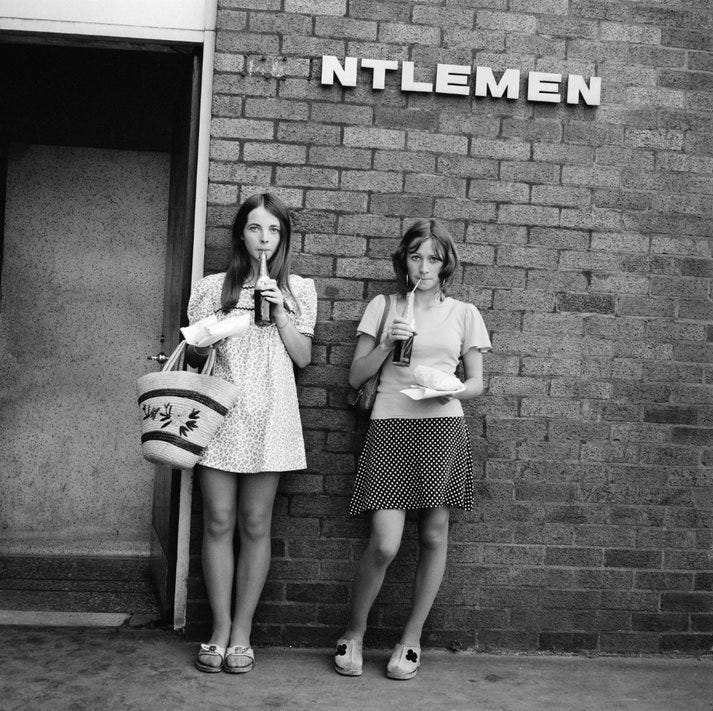

Early in the film, photographer Mik Critchlow, who himself strikingly documented the Northumberland mining communities that he grew up in, says ‘You have to be in the tribe to photograph the tribe. You have to do the same dance.’ Critchlow’s statement encapsulates the power that underpins Murtha’s images. Her photographs of the children in Elswick do not romanticise or aestheticise its decaying urban landscape: their focus is on those kids as individuals, making the best of things despite what surrounds them.

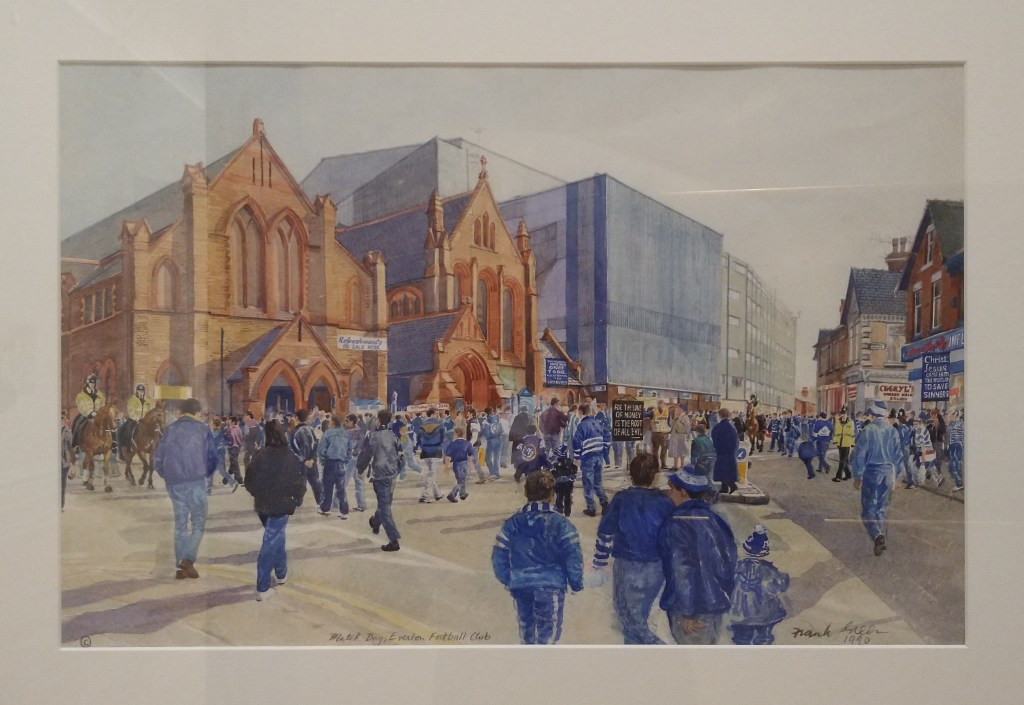

Meanwhile, her images of Juvenile Jazz Bands might, in other, outsider hands, have resulted in a simplistic celebration of a ‘quirky’ North East cultural phenomenon of military-influenced marching bands. Murtha, though, took a critical eye to these bands, questioning what she felt wasn’t an adequate substitute for the real creative opportunities working-class young people lacked. This provoked the ire of some in the community. In response, she invited her critics to a public debate. To me, this clearly demonstrates the need to commission working-class artists to document their own communities. While some might think local creatives lack critical distance, it is in fact the insider’s eye that looks deepest, understands the wider context, and can confidently critique aspects of their own culture – even if it does not always win friends. Another piece of Murtha’s writing, read by Peake, details how she came to separate herself from Side Gallery in Newcastle and won an employment dispute with them. She dismisses a ‘clique’ at the gallery that saw ‘working-class poverty as beautiful’.

Peake later reads out an Arts Council England funding application written by Murtha, detailing her plan to document the diverse, working-class community of central Middlesbrough, where she ended up living towards the end of her life. The grant application was rejected. This is intercut with readings of some of Murtha’s job applications for work in kitchens and factories, adding to her CV, ‘I am also a keen photographer’. The dispiriting, dry jargon Murtha had to adopt for job applications contrasts strikingly with her passionate writing about photography and the subjects that she was covering.

Watching TISH in West Yorkshire, I could not help but think of Andrea Dunbar, the author of Rita, Sue and Bob Too (1982) whose early talent, difficult later life and death aged just 29 have been examined across films, books and plays, including Clio Barnard’s The Arbor (2010) and Adelle Stripe’s Black Teeth and a Brilliant Smile (2017).

As was also said of Dunbar, some of Murtha’s friends and relatives acknowledge that she could be ‘difficult’ and was someone who refused to compromise. One friend recalled how she got Murtha a teaching job in which she apparently lasted less than half a day. There, however, is the rub. We tend to admire artists who refuse to compromise in what they do – yet such tenacity is easier when you have people and things to fall back on. Dedicating yourself wholly to your creative work is so much harder when you have no external means of support – and even more so when you have caring responsibilities for others.

Working-class artists are frequently forced into situations where, if they cannot afford to invest all their time and energy in their creative work in order to get noticed by those in power, they risk being frozen out of already limited opportunities. The systems of cultural production and distribution and the critical ecosystem that influences them still take little account of how those from structurally disadvantaged backgrounds might come to creativity in later life, or might be forced to dip in and out of making art and balance it with other forms of work. Too often, talented people fall by the wayside because an inflexible system that constantly demands what is ‘new’ and ‘fresh’ to feed itself excludes those who cannot fit its narrow parameters.

There is also the matter of expectation. Artists from more privileged backgrounds often have the confidence, instilled from early childhood, that things will probably work out, that you can focus on your personal goals and that you’ll have the space and support to do so. Those from disadvantaged backgrounds frequently do not have this sense of security. Devastatingly, in the film Ella Murtha reveals that after her mother passed, she got a rebate cheque from her energy supplier. Tish was significantly in credit, but had still been afraid to put the heating on, not knowing where she might find the money in future. Conditioned, perhaps, to think that she didn’t even deserve this basic survival need. I can think of little more socially damning than this important artist – this human being – not only being denied support for her creative work for years, but dying afraid to put the heating on.

In many respects, things have got worse since Murtha’s death in 2013 for artists from working-class backgrounds trying to survive, let alone thrive, in their careers. Social security has become harder to access and harder to live on. Many regional and more accessible arts courses have been cut and fees have become prohibitive. Arts Council funding has been reduced, and many arts organisations, especially in the UK regions, are struggling badly.

Yet, there has been a growing, if overdue, interest in and critical respect for Murtha’s work. The film details that, since her death, Murtha’s photography has been collected and exhibited by Tate Britain. There has also been an increasing interest in the work of other photographers who captured working-class communities such as Mik Critchlow and Chris Killip – both of whom were interviewed for this film and are sadly no longer with us.

In part, I think this is due to the internet making these images more widely available and easier to appreciate by many more people who do not visit galleries or collect photography books. Especially as, in many cases, the work of Murtha and others documents places, people and things that are no longer with us. The passage of time, of course, also means creative work inevitably goes through a cycle of being contemporary, becoming ‘passé’ and then being appreciated once again.

But there is something else at play. Part of the reason the work of these photographers drifted out of mainstream recognition, having never been valued as fine art in their time, is that artists engaging with and exploring class and venerating working-class communities became deeply unfashionable for a time in the 1990s and 2000s. More recently, especially with the declining socio-economic situation in the UK, class – which, of course, never really went away – is back with a vengeance as a topic in mainstream discourse. Inequalities can no longer be ignored or glossed over while the numbers in poverty grow and spread far beyond the areas most gravely affected in the 1980s – those places, like Tyneside, that were the ‘canary in the mine’. Thus, the world of culture is belatedly acknowledging the power and importance of these images, what they captured, and the artists who made them.

TISH is especially resonant now, while living standards are plummeting. Though this is, of course, a different context to the mass unemployment in the 1980s, Murtha’s story did make me wonder: what artists are trying to tell the contemporary story of working-class life now, but cannot get their work seen or heard because of their socio-economic situation? Or because of a creative sector which doesn’t do enough to accommodate and support them?

In England, it seems we do a good line letting talented working-class artists down, so that they can barely make work, or at least none that is seen or heard widely. Then, after they are dead and gone, finally appreciating them. It’s easier to do that, I guess. But how many artists don’t get ‘rediscovered’ like this? How much working-class creativity and history are lost? How many people don’t even get the opportunity to create in the first place?

TISH is a moving, arresting documentary. One that should cement the importance of Tish Murtha’s work, and of Paul Sng as a documentarian. An even greater tribute to Murtha, though, would be to appreciate and support working-class artists while they’re still alive.

This piece was published by New Critique in December 2023.