By Kenn Taylor

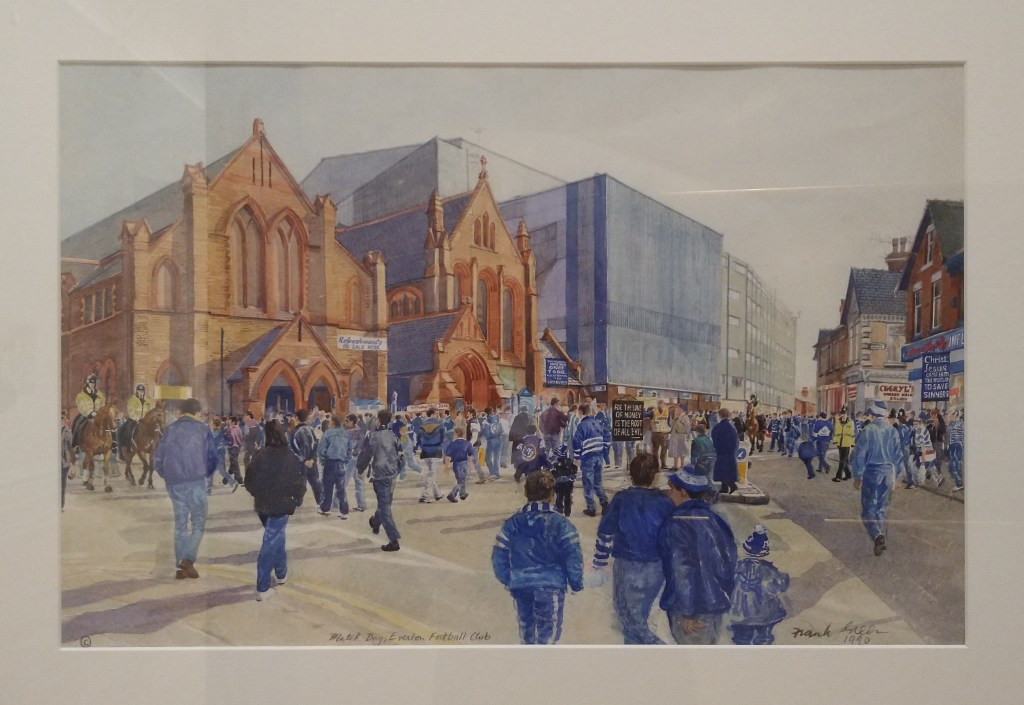

I grew up on Merseyside in the 1980s and 90s, when this region around Liverpool found itself on the extreme end of the UK’s wave of industrial decline in that period. This had a profound effect on my working-class family and community, and it shaped the way I think ever since.

Later, a period of new investment in culture and heritage in the area as a form of urban regeneration, coupled with increasing access to higher education, enabled me to work in creative fields not remotely accessible to my parents.

Yet this very access exposed me to the hollowness of some of these changes. Moving through different kinds of cultural work showed me how few working-class people worked in those sectors, except in the poorest paid service positions. It also made clear why their absence mattered. Rather than representing the experiences of working-class communities, many cultural productions treated them as ‘other’. Too often, they used and patronised the working class.

As I have written in the Journal of Class and Culture, most coverage of post-industrial communities comes from outsiders looking in. Their narratives often veer between relentlessly negative, stereotype-ridden stories and patronising ‘boosterist’ coverage, with all subtlety absent. On the rare occasions when people from such communities get to tell their own stories, they can be distorted by those who dominate and control the platforms where they appear.

My experience gave me an interest in the work of other practitioners who grew up in post-industrial communities had training which enabled them to work in creative fields, and then spent at least part of their energy drawing attention to where they came from. Many of these cultural workers have struggled to ensure their insider perspective is heard by a wider audience.

A good example is the 2021 short film Made in Doncaster by artist and writer Rachel Horne. The Guardian newspaper sent its ‘Anywhere but Westminster’ team to cover the Yorkshire city of Doncaster, and they invited Horne to be a subject of their film. Editor of a long running local zine, Doncopolitan, Horne responded with a challenge: if you want to make a film about the area, we’ll make it together. This attracted a great deal of positive attention nationally and highlighted Horne’s efforts to create a local media voice in the face of the decline of regional newspapers and radio. That decline has made journalism a more elitist trade and reduced opportunities for people living in disadvantaged regions to provide a counterpoint to skewed coverage from national outlets.

The film shows Horne’s determined efforts to feature the voices of people like her and provide visibility for the talent and creativity of the community, not just its problems. As Horne explains, solutions to those problems need to be led from within: “We’re resilient and we don’t need to be patronised. We don’t need experts coming in telling us how to fix things. We want to fix things on our own terms and that’s the way it’s going to work.”

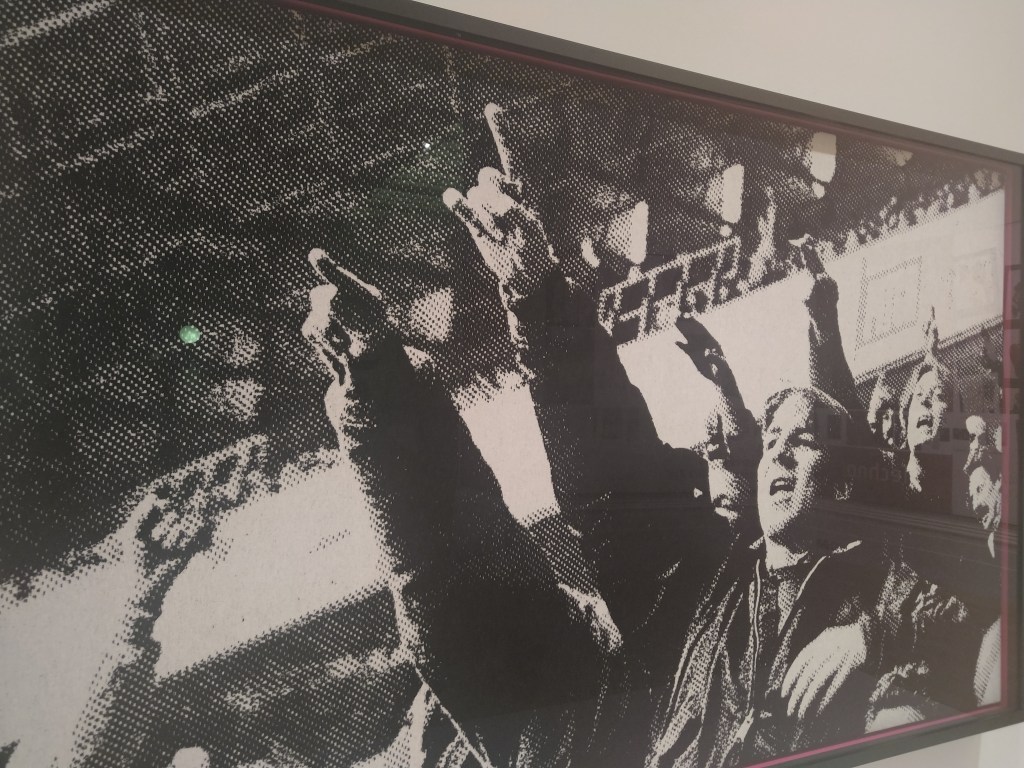

In the film, Horne emphasizes the influence of the 1984-85 Miners’ Strike: “I was born in the miners’ strike. I lived through that whole collapse. It’s not just unemployment it’s like the whole culture went and then you’ve got ten years of austerity.” That influence is also clear in Sherwood, a 2022 BBC drama series created by writer James Graham who grew up in a mining village outside Nottingham, the setting for the series. This powerful drama explores a range of themes, including how all its characters are haunted, one way or another, by the miner’s strike and the subsequent disappearance of the coal industry in the area.

One of the tragedies of my lifetime is that the damage caused by the evacuation of industry without replacement, something once contained to certain areas, has, rather than being remedied in such places, instead gone on to consume much of UK. Sherwood highlights what many in the British establishment have been trying to gloss over and forget since the 1980s. As one of its principal characters puts it, “They didn’t care about us then, the don’t care about us now, they just use us. Look at what they still call us, what we call ourselves. A former mining town. Why? Post-industrial. How the hell are we meant to move on from that when even the way we talk about ourselves is by what we aren’t anymore? How are my grandkids meant to imagine a future beyond that, eh?” The spectre of deindustrialisation haunts Britain.

No other developed country has de-industrialised to the extent that Britain has. And artists like Horne and Graham, who grew up in deindustrialised places, can help us understand what happened and what life is like in these communities now, far better than the misrepresentations projected on to them by others.

Graham, Horne, and I were able to attend university, where we honed our abilities to probe into and communicate about such things, drawing on direct experiences. The expansion in higher education from the 1960s to the 2000s gave us increased access to power to ask difficult questions and express the complex truths of our experiences and our communities. But such access, especially in the arts and humanities, is now contracting in the UK. In particular at the universities with the highest proportion of working-class students. Like us, young people from such communities today not only have limited local employment options, but they also have fewer educational opportunities.

Both Made in Doncaster and Sherwood contain hope for the potential of working-class cultures and communities in post-industrial areas. That hope comes from the resilience of people in such communities despite everything thrown at them. It’s a hope though mixed with an ambiguity and a degree of cynicism that comes from having seen so little change for the better at a fundamental level over several decades. If we want anything to improve in future, voices like these must be heard more widely.

This piece was published by Working Class Perspectives in May 2023. It is taken from a paper I presented at the Transnationalizing Deindustrialization Studies: Deindustrialization and the Politics of Our Time (DePOT) 2022 Conference, Bochum, Germany, August 17-20, 2022.