By Kenn Taylor

“An epoch or a civilization cannot be prevented from breathing its last. A natural process that happens to all flesh and all human manifestations cannot be arrested. You can only wring your hands and utter a beautiful swan song.”

Renee Winegarten

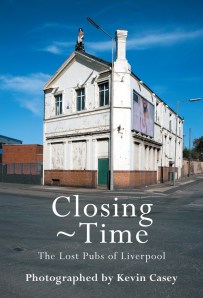

THROUGHOUT THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY, the medium has often been used as a way of capturing what will soon be lost.There is a long tradition of photographers trying to preserve something of both landscapes and people at the point before they are gone forever. Kevin Casey’s images of abandoned public houses in Liverpool fall into this tradition.

These photographs are a systematic archive of the disappearance of what were once, both culturally and architecturally, a key feature of local communities across the country. They are also a lament, and a tribute, to what was contained within these public houses. After all, though we may admire old pubs for their cornices, brass rails, wood panelling and frosted glass, it was the life and community spirit that once existed within these now abandoned buildings that makes most people nostalgic for them.

These photographs are also a stark reminder of the urban decay that, far from being turned around by the regeneration schemes of the 1990s and 2000s, has continued apace in most areas of Britain. The uniformity in composition and the repetition of form in these images bring to mind the work of German photographers, Bernd and Hilla Becher. Except that while, in the 1960s, the Becher’s documented post-war industrial expansion and the increase of automation, here Casey documents the decline of Western industrial culture and the communities that relied on it. Yet, despite the frank depiction of the current state of these buildings, there is also a sense of empathy in the images. An empathy that could only come from a photographer native to Liverpool who had personally witnessed the decline of many of these pubs and their communities.

The number of pubs in the UK has long been in decline, as patterns of life and work have changed. However, the rate of closure has increased in recent years, with over 6,000 shutting down since 2005. Those that remain are now being battered on all fronts. The smoking ban, cheap alcohol in supermarkets, high tax rates on alcohol, problems with entertainment licences, big-money video gambling machines in bookmakers and the inability to tap into the lucrative pub/restaurant market have all hit many local pubs. Added to this is the domination of the pub industry by large, ruthless pub companies, keen to maximise their returns on supply charges and rent, leaving tenants struggling to make a profit. In turn, these power blocks of pub companies, with their collective buying and bargaining powers, are squeezing out the smaller operators. Above all, the deep recession we are currently experiencing, has driven down money for leisure right across the social strata, making people rethink how they spend their more limited incomes.

Pub closures in the UK peaked in 2008 and, although levels have since reduced, the number of pubs going out of business remains depressing. At the time of writing, closures are running at the rate of 39 a week, with a total of 2,365 pubs lost during the whole of 2009. This shocking rate raises a variety of big issues, from job losses and reduced tax revenue to abandoned real estate rotting away, but the effects are felt most in the communities that these pubs once served.

The Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA) estimates about 40,000 of the UK’s 60,000 public houses are ‘community pubs’ – those which serve the people who live or work around them. CAMRA suggests that the benefits of having a pub in your local area include support for local charities and sports teams, having a space for social interaction and providing a place to drink in a safe, regulated and controlled environment. This shows the profound effect the loss of a local pub can have on a community although we should also be careful not to romanticise the local pub entirely. It is easy to look back with rose-tinted spectacles at the glazed tiles, wood-block flooring and frosted glass and forget that the tiles and wood block flooring were easier to wipe the blood and spit off and the frosted glass meant that the man of the house could drink away his wages unnoticed while his wife and children starved.

Even today, it must be acknowledged that pubs can also be a blight on a community, and many welcome the shutting-down of problem establishments in their area. There has been a history of some pubs being centres for criminal gangs, drug dealing and violent incidents, not to mention anti-social behaviour, vandalism and theft from those leaving the pub at the end of the night. For some urban communities, these pubs add to their many and complex problems, not help solve them.

This highlights the fact that the photographs in this book also reflect something wider, that of the changing nature of Britain’s urban communities in the 21st Century. From the Great Depression of the 1930s, through the 1960s slum clearances to the present day, photographers have been drawn to the inner-city and its people. Liverpool, in particular, with its striking urban changes, has often been a favourite subject.

So what does this latest survey of our changing urban environment tell us? What else can we see in the landscape where these abandoned pubs sit? It is not a happy story wasteland, boarded-up houses, crumbling industrial buildings, local shops as abandoned as the pubs. In some photographs, the signs of communities clinging on despite all of this can be seen, but nowhere in these pictures is thriving and, in many, the communities themselves are struggling as badly as the pubs on their corners.

It may not be a happy story, but it conveys a truth that reflects not just on Liverpool but much of the UK. These dead pubs are simply the most prominent examples of dying communities, a dying culture even. For generations, cities like Liverpool grew on the back of their commerce and industry. Now, as the industries have declined, the culture and way of life that surrounded them has slowly ebbed away, despite the best efforts of many within these communities. The Victorian architecture of the pubs, and the rows of terraced houses and industrial buildings that usually surround them, are a marker of a time past, a culture now gone, that will soon be as much a memory as the rural and agricultural Britain that the Industrial Revolution replaced.

As patterns of life and work change so inevitably will behaviour and culture. The consumer dream of choice that Britain has bought into has reduced the need for community pubs. Fifty years ago, in cramped family-filled houses with no central heating and limited home entertainment, the pub was one of the few escapes for many.

Now, why go the pub when you can buy cheap alcohol from the local supermarket, relax on your sofa, watch the match on your own big-screen television or play computer games, in the comfort of your own home for as late as you want?

There is, however, also something of a fightback on behalf of pubs. There have been many innovative solutions to stave off closures including co-operative community takeovers with pubs also taking on the role of general stores, cafes and even post offices. Most of these successes, however, have been in rural communities, often home to a wealthy commuting population. A CAMRA survey meanwhile suggests that over 80% of pub closures are urban.

In other UK cities, closed-down pubs have found new uses, everything from restaurants to money transfer facilities and even a canoe centre. There are some examples in Liverpool – one former pub in Seaforth has now found a new life as a branch of KFC, while another, The Clock in Everton, is now a successful community centre. Many more lie empty though, symptomatic of Liverpool’s perpetual economic malaise. Can these measures to save pubs succeed when the culture pub-going was based on has fundamentally changed? Can we, or do even want to, preserve in aspic what was a once-lively culture that is now in decline? Or, should we just accept that things will always change, and that there is a different future for drinking establishments? That will concern the traditionalists but let us remember that the grand ‘gin palace’ pubs we now revere, like The Vines and The Philharmonic in Liverpool, were viewed in similar ways by Victorian and Edwardian society as today’s media tend to view our ‘vertical drinking establishments’ – as garish and decadent places whose false glitz and glamour seduces the lower-classes to drink and doom.

Today, most young people in Merseyside prefer drinking in city centre-based bars and clubs and this poses problems. As much as drunken and violent behaviour happened in local pubs, the fact that they were still located within the communities that people lived in, with different generations drinking together, usually put a brake on such outbursts. City centre bars don’t have this self-regulation, and it has been suggested by the police that areas of concentrated bar development, such as Concert Square in Liverpool, actually intensify unruly behaviour by containing a large number of drinkers in a small area.

Concert Square was one of the pioneering developments in the UK for modern bars with dance-floors and outside drinking areas. Its developers advocated they wanted to give Liverpool the kind of ‘sophisticated’ outside drinking area that they had seen in Europe, and the development was replicated throughout the UK. Any visitor to Concert Square on a Saturday night could easily see that this has not come to pass, and that the violence and destruction that are features of weekend nights across the UK is at least partially a result of this failed aim. British culture is simply not like that of continental Europe and introducing 24 hour city-centre drinking will not covert British drinkers to slowly sipping a red wine on the terrace.

Liverpool might be the focus for Casey’s photographs but this city is merely at the extreme end of a national phenomenon. Social disorder and urban decay is prevalent, in varying degrees, from Burnley to Nottingham, Stoke to Newcastle, and Swansea to Ipswich. Leisure-led regeneration has been trumpeted as one of the answers to problems of urban decline since the 1980s but, once again, Liverpool has shown the rest of the country the error of its ways.

Since the credit crunch, the leisure-led regeneration myth has largely been debunked. Luxury flats, art galleries and shopping centres may improve cities but they will not, on their own, renew the communities that live next to them and, without wealthy residents to move into these new developments, they will not even replace those communities as they have done in places like London and New York.

Post-industrial cities of the kind that are now found throughout Britain are a relatively recent development. The future of urban areas, like the ones Casey has photographed, is uncertain. Many of these places, such as Kensington, Anfield and Seaforth, were once fields or sand dunes. In these pictures we can see grass and foliage slowly reclaiming what was once built over in the rush for a growth that is now retreating. Perhaps, one day, these streets will be fields and dunes again. Maybe the glass and steel bars that have transformed our city centres will eventually spill out into the districts that surround them. Yet, all of the issues that surround climate change seem to indicate that we could once again become more dependent on community. Most people seem to agree that we have lost something in our consumer-led, individualist culture that is unsustainable. Perhaps, then, the local pub has a future?

Indeed, it must also be pointed out that, despite this photographic survey, CAMRA recognises that Liverpool has, perhaps, the best collection of traditional pubs in the UK outside of London, though most are in the town centre and the wealthier suburbs.

The irony is that Liverpool’s poverty has actually helped preserve many of these pubs, which in wealthier cities would have been swept away by money-generating developments. These pubs, coupled with Liverpool being one of the few cities to retain an independent local brewery, Cains, has made the city a hotspot for ‘real ale tourism’ – a growth area for pubs. Real ale fans tend to be financially better off and might keep these pubs alive. Ironic, perhaps, that in the 1980s, it was the middle classes who appeared to favour the new style of bars over the traditional working-class pub. Whatever happens, this photographic survey of pubs, of Liverpool, of Britain’s urban environment in 2010, will remain a poignant document of its particular time. Casey’s efforts in scouring Merseyside for these buildings, in some cases on the day they were being demolished, are to be admired and have resulted in an important book that will be increasingly appreciated as more of our traditional landscape is lost in the coming years.

This essay was one of several pieces of writing by me that appeared in the book Closing Time (ISBN 9781904438854) published by Bluecoat Press in December 2010.